The Myth of Unstable Surface Training (And What to do Instead)

My favorite computer game growing up was "The Oregon Trail." I would play one version in the computer lab* in Elementary school and another version at home. Yes, I loved it THAT much.

(*On that note, do they still have computer labs in school? I hope so, because all I can think of is an annoying, pretentious commercial where one girls asks "What's a computer?")

Anyway, why did I love "The Trail" so much? Because the game's choose-you-own-adventure format, and against-all-odds mentality (even when playing on the "easy" level), are a combination that's still uniquely suited to my personality.

But I realized this week that "The Oregon Trail" serves as a great analogy to how many individuals view their own exercise and fitness programs. Go with me on this one.

With all of the noise on social media, and so many paths to choose from, most people are left to navigate the fitness industry for themselves. Only in this case, they're not deciding between the Columbia River Gorge or Barlow Road. Instead, they're left to decide: running or strength training? Crossfit, Flywheel, or Barre classes?

And not only are these fitness decisions different than the game, so too are the stakes - you won't die from dysentery, but you may fail to see results despite all of your time and effort.

With that in mind, I'd like to address a fitness trend that has died off within the industry a few years ago, but still has some traction among some trainers: unstable surface training. Otherwise known as standing on bosu balls, airex pads, or other cushion-like substances all in the name of "functional" training.

As with any exercise or tool, there's a specific time and place that unstable surface training can offer value. In a rehabilitation setting, under the eye of an expert practitioner, it can elicit the specific adaptations that professional is looking for.

But for 98% of people that are looking to get stronger, lose weight, and look better - your time and effort is better spent on the hard ground. Here's why.

The History

There are better ways to spend your time than with an unstable surface on top of an unstable surface.

The argument for unstable surface training is that it triggers greater muscle activation than when someone is on stable ground. These claims are backed by some research, and it matches anecdotal evidence from anyone that's spent time on a bosu or stability ball. Our brain and body are trying to find stability wherever we can find it, and we may feel more of a "burn" than when we do the same exercise on normal ground.

In rehab settings, this can be effective tool. But in the hunt for greater muscle activation, we need to ask ourselves: is this actually going to help people achieve their goals?

It doesn't. It's usually eyewash.

That's because 1) increasing muscle activation, and 2) using it effectively to improve someone's program, fitness, or quality of life outside the gym are two different things. And when you look at the comparative research, it backs up my point.

All Muscle Activation is not Created Equal

Of the multiple papers that have been published (one, two, and three for example), there's a recurring theme: unstable surface training may or may not yield results. And if they do, they pale in comparison to the results seen on stable ground.

The question is: why?

It all comes down to specificity.

The key to understanding this principle is that in order to improve our squats, we need to squat. We can't expect running, push-ups, and chin-ups to improve our squat - only squats themselves.

Specificity at it's finest. I'd be willing to bet he did zero training on a bosu ball.

The same principle can be applied to training for a marathon. In order to get better at running, people need to run. So while I often advise individuals to limit their mileage when training for a marathon - due to injury risk, injury history, quality of running technique, overall time management - they still need to run. They can't expect all of their hard work in the weight room to translate to a faster marathon time without running - it's different energy systems, movements, and different stress on our brain.

How does this apply to unstable surface training? Because we live in a world of stable surfaces! We may see more muscle activation in stabilizing muscles when we're using an unstable surface, but our brain and body perform and compensate differently. Time spent training on this surface is not going to carryover to how we interact with the world around us. Further, training on an unstable surface often poses a greater risk of falling and injury, which often means reduced training time.

That's why the ingredients for body composition and physique change remain the same: big, compound movements that give you the most efficient value for your time. This means squats, deadlifts, swings/snatches/other kettlebell related exercises, push-ups, chin-ups, etc.

Because here's the secret: if you perform these movements with grace and great technique, you're going to see improvements in your balance and stabilizers, while also getting noticeably stronger. And isn't that what most people are chasing?

2 Factors to Increase Your Stability

Still, if you want to improve your balance and stability on one leg, there are safer alternatives than using unstable surfaces. Here are two ways to get you there.

1. Improve your strength on two legs.

Single leg training has received a lot of attention and it should. It's an important part of my programming for myself, my clients, and what I'll generally advise everyone to put into their program at some point.

Why isn't this figure wearing any clothing? These are life's big questions.

However, you need to build your strength one plane at a time.

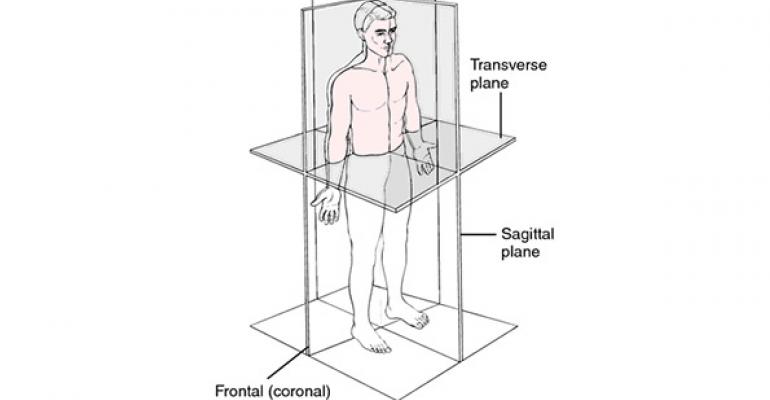

In this case, we need to build the sagittal plane first - which are exercises performed on two legs and go in a front to back direction. Some examples are goblet squats, deadlifts, two handed swings, etc.

From the way we manage pressure and air, to the way we stand on one leg, this is all determined by how we control the sagittal plane. And while there is a such a thing as being "too sagittal," it's a great place to start for 97% of people who want to improve their balance.

2. Start implementing "split stance" variations

When most people decide to start incorporating single leg activity, they often progress themselves too quickly and it doesn't end well. They either lack the strength in an exercise like a single leg squat, or they feel completely off balance like a baby Giraffe.

And last I checked, looking like a baby Giraffe was not a good thing.

The reason many people face these issues is that they often skip over an entire category of exercises called "split stance." This stance allows us to manage the sagittal plane (mentioned above), while beginning to incorporate the frontal plane. Mastering split stance activities is a big step for making the transition to true single leg exercises like a pistol squat (often seen as the pinnacle of balance).

What are some examples of split stance work? Here's both a squat and deadlift variation.

Slowly adding these in will really help your balance, and also make you feel more athletic. And isn't that what we all want?